Offshore Wind Support Schemes - A New Way of Working - Part 2

How can we tailor our finite resources and market mechanisms, for flexible and sustainable whole sector growth in renewables...

Introduction

This is Part 2 on Offshore Wind Support Schemes. You can check back into Part 1 here. In Part 1 we explored the schemes implemented to support low-carbon renewable generation in the UK over the last 35 years.

In order to move forward effectively as our Clean Power 2030 target looms into view, we must onboard learnings and mistakes from the past. Not all our support schemes have been sucessful; in fact some have hindered significant aspects of the UK's supply chain and wider sector development.

We have it within our grasp to innovate and be expansive in our thinking and strategic delivery. Compared to the legacy support schemes, from the original NFFO, to ROC and now CfD - which is 10 years old already - we have the capability to run and manage more agile, balanced and effective mechanisms.

Offshore Wind Support Mechanisms need to evolve; just as the needs of the market, supply chain, technology and grid develop over time.

Virtual Resource Model

The proposed Virtual Resource Model allows for a defined support volume, lower risk, direct open access to the market, and competition to ensure the lowest cost.

The mechanism is based on an economic structure that attributes socialised value to the resource.

This provides an efficient mechanism that stimulates the market, enabling it to be efficient through minimal intervention, while maintaining competition.

It is critical for the future of the industry, renewable generation, and the success of offshore wind in the eyes of the UK's key stakeholders - it has to give value for the taxpayer and consumers, delivering low-cost, low-carbon energy.

Desirable Traits for Market Support Mechanisms

What have we learned from our past experiences in the UK and other countries as we aim to develop new markets and technologies? The following are seen as the key desirable traits for any market support mechanism:

- Defined Budget - full utilisation of the budget with no budget overrun risk

- Direct Access to Market for Developers - no centralised decision making, and no risk of incurring additional cost due to competitor mistakes. e.g. underbidding and project non-delivery

- Competitive Process - ensure efficiency within the market to facilitate positive outcomes for all stakeholders

- Ability to Drive Specific Policy Positions - growth, innovation or grid stability, geared to suit the needs of the sector and period

- No Punitive Traits - support is support, no loss of value that other market players can access

- Low Administrative Costs - low cost to partake in the mechanism, for both government and developers

- No Additional Prerequisites - if a project is delivering the desired outcome, it should be able to access support

- Visibility of Demand for the Whole of the Supply Chain - no unpredictable centrally defined “veils” obscuring demand and adding uncertainty to the procurement process

Economic Context and Perspective

We believe we have identified a model, based on the 1930’s discussions between the economists Keynes and Hayek. Where Keynes rightly identified that government has a role to ensure liquidity in the market, and Hayek rightly identified that government needs to be careful with such actions - to ensure it's through the least interventionist mechanism possible.

It further takes inspiration from the adage of Keynes:

Purely burying gold would stimulate the market through people buying shovels

The similarities to that model can be drawn from the offshore oil and gas industry exploiting the buried resource of hydrocarbons.

As a new technology and nascent sector, offshore wind was not able to compete freely within the market and so required additional support. Our argument is that support should be treated as a resource - hence the Virtual Resource Model.

The Market Rules

The Virtual Resource Model is predicated on the basis of the market being a much more efficient arbitrage agent than any centralised decision authority. It aims to achieve the most efficient balance between dispatched volume and cost of electricity for an allotted budget. It removes the forecast sensitivity within the process, sets price by the lowest cost entrant to the market, which ensures the most efficient participants are the most profitable. Critically it also gives the supply chain visibility of demand and therefore an ability to plan order books to facilitate investment in increasing supply capacity.

The basic principles of the mechanism are:

Flexible Resources

The VRM is a stand alone mechanism with direct access, and to facilitate ease of uptake, could easily work alongside alternative support mechanisms.

The government could define that a portion of any Phase / Allocation Round is available to projects choosing to access the VRM as opposed to the CfD, based on the percentage of projects opting to go that route. e.g. if for the next round of support 10% of projects said they would prefer to use the VRM over the CfD then allocating 10% of the budgeted support to the VRM, would provide those projects the requested support, and allow the government to A/B test the mechanism.

Key VRM Advantages

- Clearly defines - the amount of support provided to the market, with no risk of exceeding or not achieving that level of support.

- Direct access - to the market for developers.

- Price support - for power over and above the raw market price.

- Eliminates - non-delivery risk; no project can lose an allocation round, incuring cost, to a winning project that does not progress to construction.

- Low Impact - does not require administration of the allocation process.

- Reduces Time - allocating contracts, allowing the projects to progress at lowest cost.

- Activates Supply Chain - ensures early engagement with projects as there is no go / no-go decision, in the way of construction.

- Removes Requirements - for a generator to take part in the traded market; they are free to sell their power under a PPA or other mechanism.

- Flexible Modification - it can be easily modified over time to achieve desired goals of renewable energy deployment, supply chain development, innovation, etc.

- Lowest Price Setter - it sets the price of the support awarded to projects based on the last (lowest cost) entrant to the market

- Multi Vector - can apply across technologies, including storage. The weightings can be varied depending on the required level of allocated policy support, and on deployment profiles.

- Smooths - the delivery pipeline; with no allocation round developers are free to negotiate supply chain contracts without a batch of competitors trying to do so at the same time.

Implementing Weightings

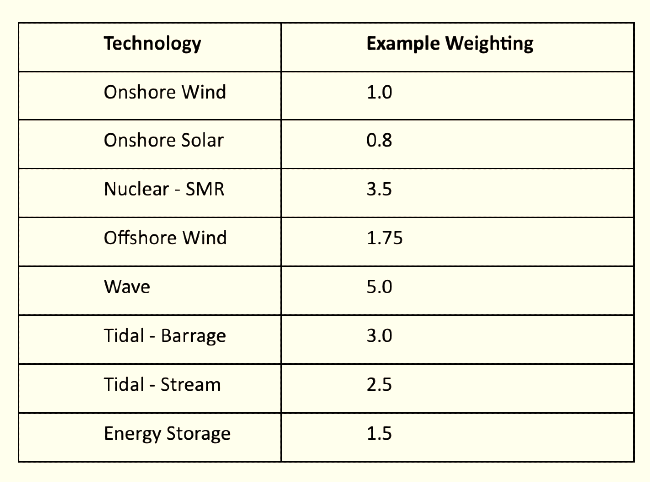

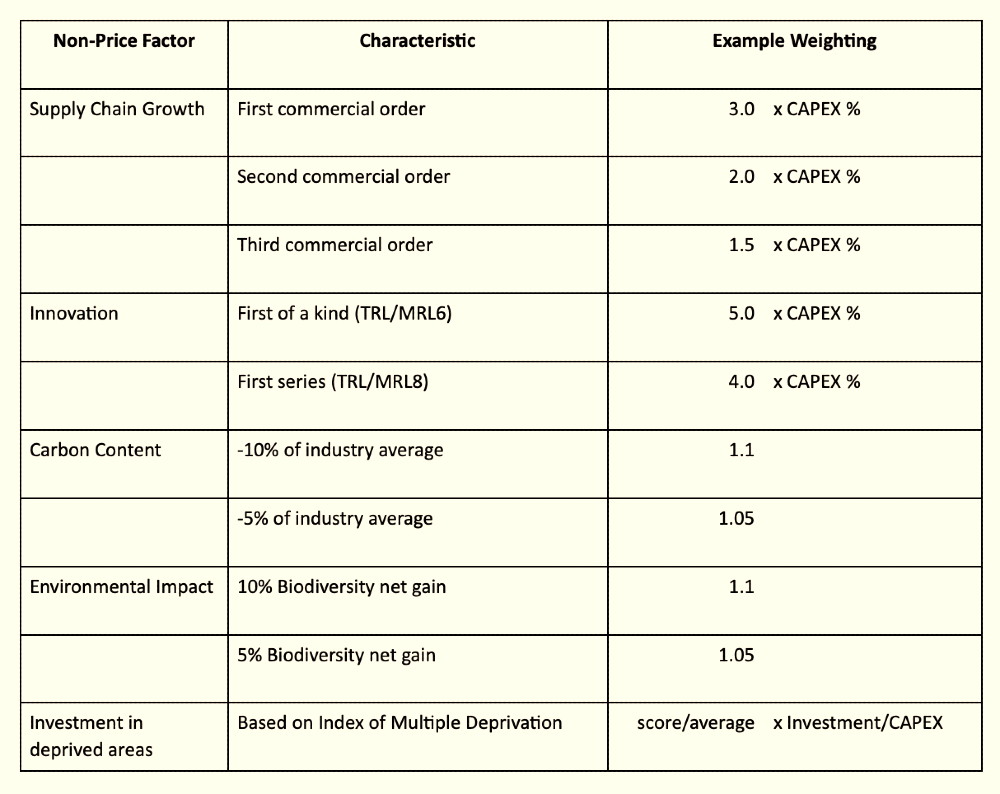

The VRM can be weighted to facilitate differing technologies and the government’s non-price factor policies, for a simplified example technology weightings could be

While Non-Price Factors weightings may be:

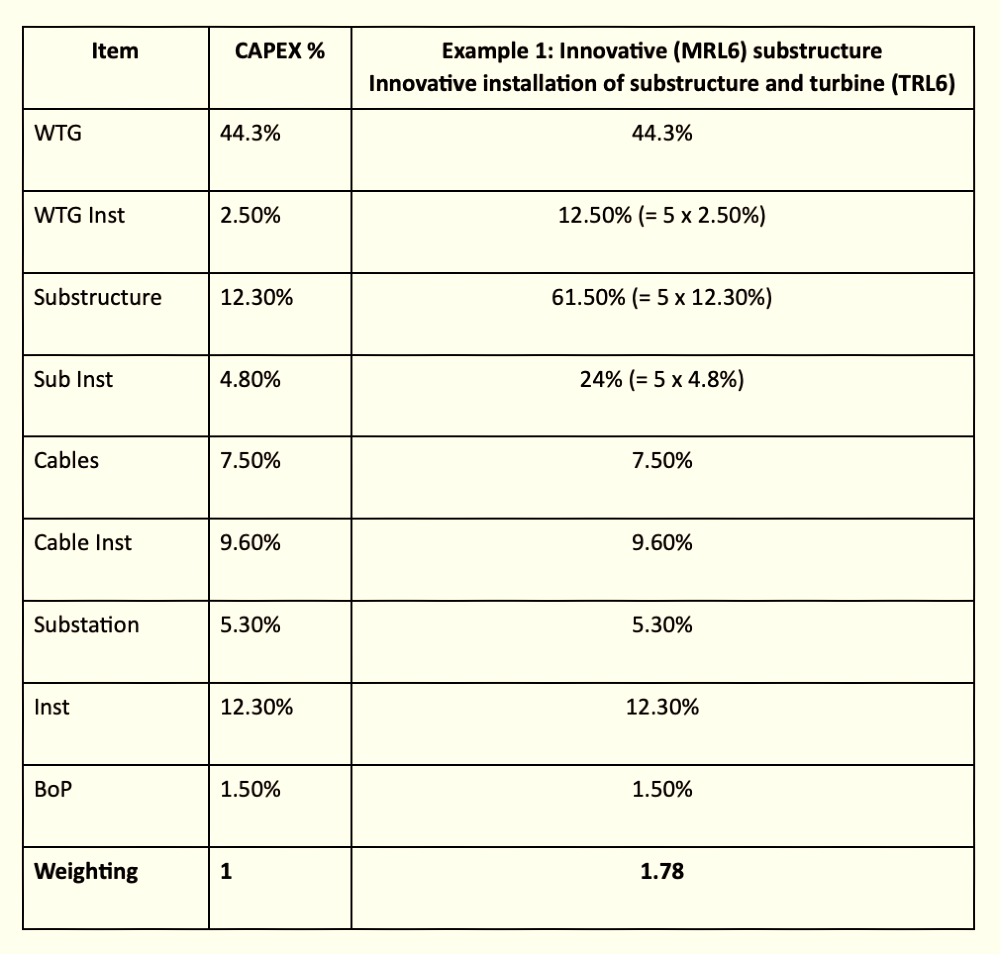

To illustrate the above for a project focused on innovation, using CAPEX for simple modeling:

Model Advantages

The advantage of such a model is that innovation and supply chain growth in significant CAPEX areas is rewarded accordingly. As CAPEX varies across projects, using the project's own CAPEX model for calculating the weighting ensures that the mechanism is efficient.

Developers are highly motivated to reduce costs; they should be focused on the areas of most significant savings. Those savings minimise the increase in the weighting due to their reducing percentage of total CAPEX, thereby creating a competitive structure that always seeks to minimise CAPEX.

While the above example uses CAPEX for simplicity, the key factor of relevance is LCoE. Applying the model to LCoE allows for innovation in maintenance and operational models, maintenance and operational supply chain growth, and potentially even issues like innovative financing structures, e.g. horizontal splits of the asset and long-term leasing of BoP.

Multi Vector Example

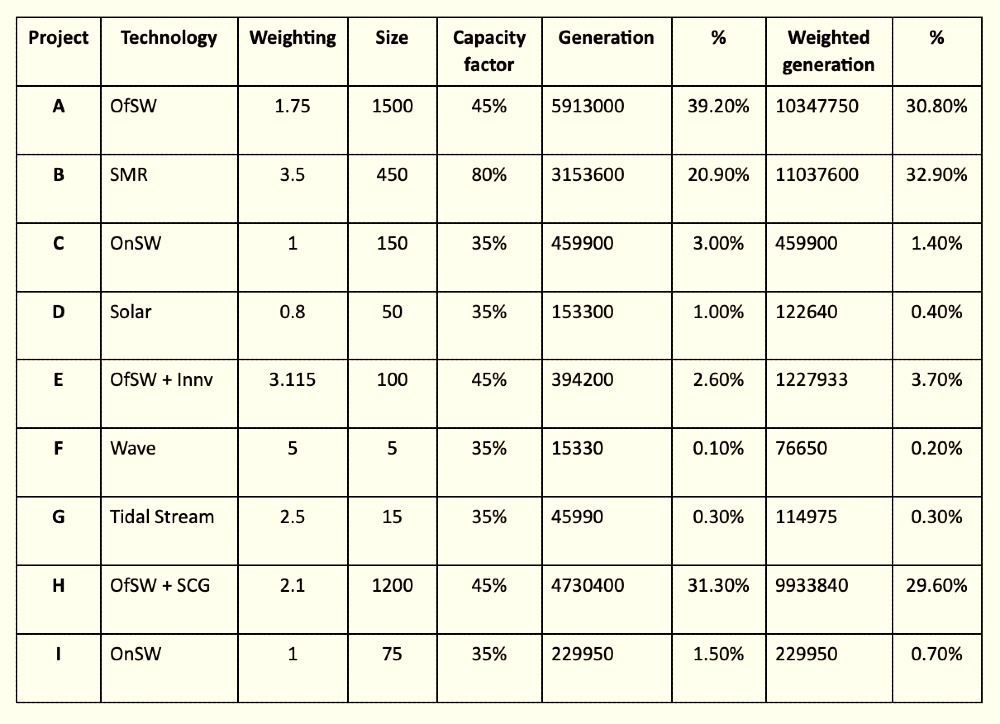

As a snapshot summary of how the weightings could work for different projects with different technologies and non-price factors, the following table looks at how the percentage drawdown of any one project, is adjusted with the various weightings:

The government would be able to adjust weightings between commissioning periods to vary the market signal based on the rollout of all low-carbon technologies, the mix within the grid, the maturity of that technology, etc.

However, for any constructed asset, the weighting set at the point of commissioning would remain the same. For example, if more storage were to be needed (or distributed load shedding, vehicle-to-grid, etc.), then the weightings for those technologies could be increased.

Similarly, should delivery fall behind targets, the government would be able to recognise such and adjust the total volume of support for future projects in the confidence that the competitive process would result in the last/lowest cost entrant to the market, setting the level of support.

To hit decarbonisation targets early, development is of significant interest; at the same time, some technologies (e.g. nuclear, tidal barrage) require longer periods of support. The profile of the budget could be set based on the government's expectations of what technologies will be built and goals for the generation mix.

To facilitate the need to prioritise grid management and non-price factors, etc. the government could introduce commissioning batches or change weightings, as required between accounting periods.

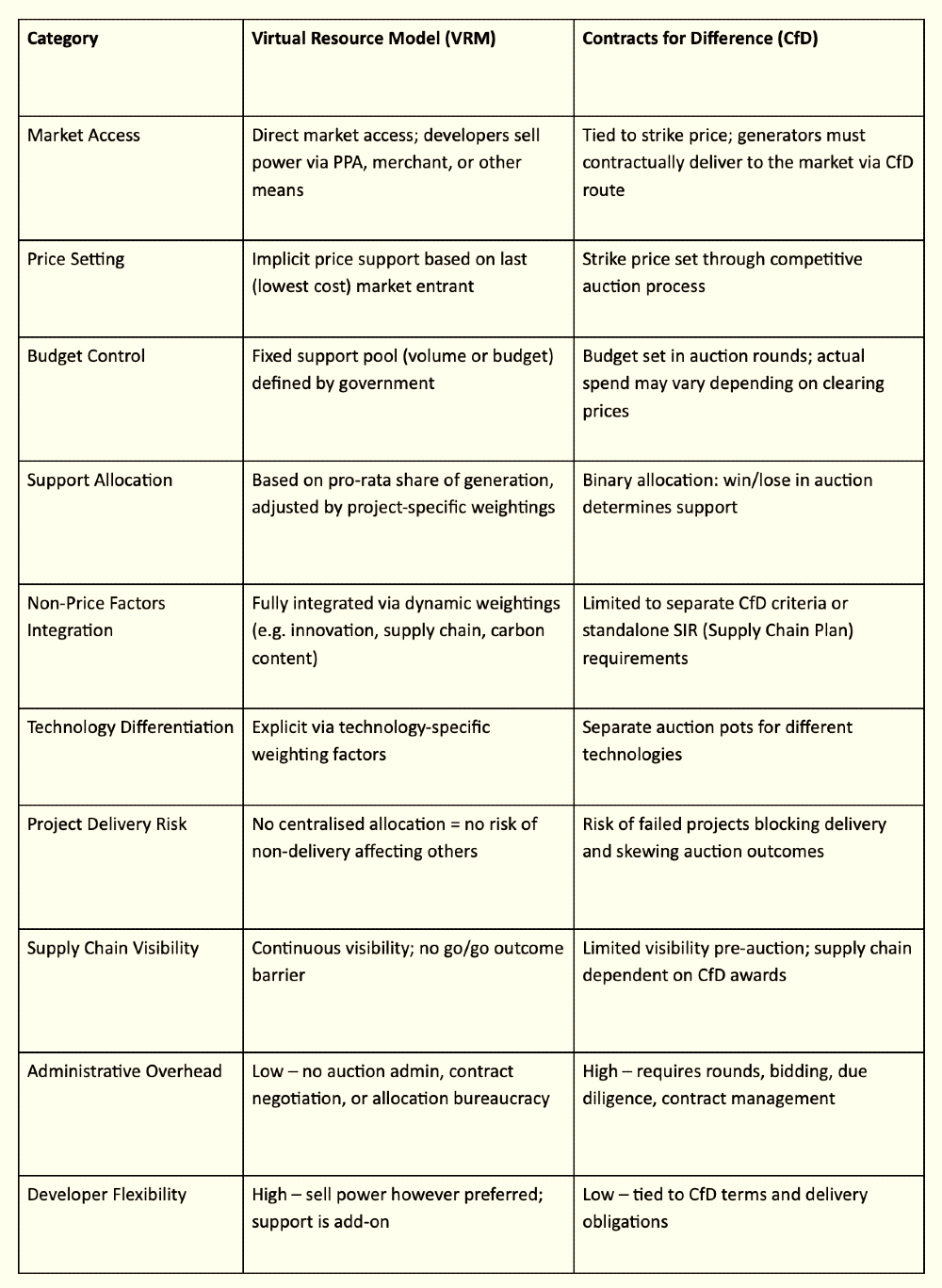

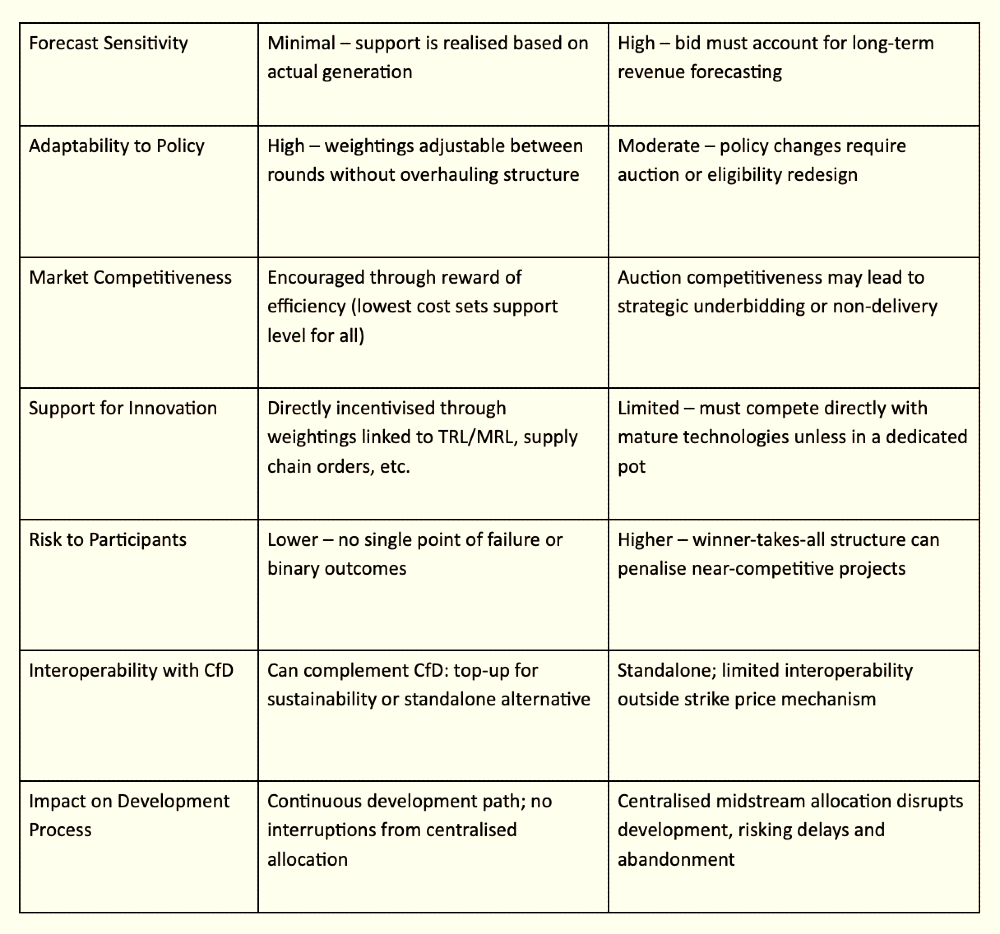

Comparison with CfD

Bringing togthers the comparartive analysis with the incumbent CfD, highlights the key differeantiation and factors of VRM's enhancement - unlocking a more agile and relevant market-based mechanism.

Moving Forward into AR7 and Beyond

As I share my thoughts on a new way forward for renewable support mechanisms with the Virtual Resource Model, a significant part of the UK renewables industry are awaiting imminent results from the CfD allocation round AR7. I’m not a supporter of the CfD mechanism - my further perspectives on its limitations in Part 1.

By opening the VRM detail for discussion and public visibility, I hope that more key stakeholders are open to consider further dialogue on the alternative I propose.

While everyone who has taken part in the AR7 are clearly invested in the results, the reality is (even if the government is ambitious/generous in its allocation) not all can win. Some of those who won’t win, may have lost out to projects that won’t get built - we’ve seen it before with Norfolk Boreas and Hornsea 4 being abandoned, and Hornsea 3, East Anglia 3, Inch Cape, and Moray West being downsized after winning their CfDs.

That is the crux of the problem; as a developer, losing to a project that doesn’t get built is insult upon injury. Not only has your project, in which you have invested hundreds of millions of pounds, not able to progress to market (while your debt is accruing further debt interest) but the project you lost out to isn’t even going to get built!

The reality is that when governments make decisions they make mistakes, even when those decisions are outsourced. Asking private companies to subsidise the cost of those mistakes is unacceptable.

Unfortunately the conversation about whether the CfD is the right tool for the job isn’t even currently on the table. Not only that but the contagion is spreading - just as the UK spread the travesty that is unbundling (separating transmission assets from generation), we are now infecting everyone with the CfD.

Germany, who possibly have suffered most from the UK’s championing of unbundling - which the Germans originally opposed pre-Brexit, are seriously thinking of implementing the CfD into Energiewende - historically having relied on a feed-in tariff system under the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG).

The concept that companies can guarantee prices is addictive for goverments; the question as to whether they should let them, hasn’t even got a look in.

About the Author

Matt Bleasdale

A consultant to the Offshore Wind sector, Matt has a weath of experience from a career begining in subsea and later with project and contract management with E.ON, London Array and The Crown Estate. His own consulting activities have led him to work with organisation such as Orsted, Bureau Veritas, and Iberdrola.

You can follow Matt on LinkedIn:

Matt Bleasdale - Offshore Wind Consultant